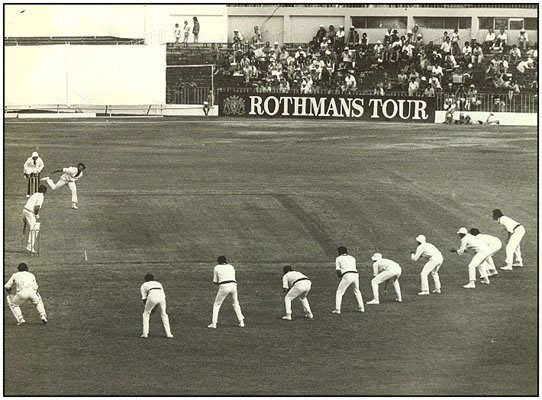

It so happened that during my fourth year at IIT there was an ODI series between Australia and Zimbabwe – a classic case of ruthless extermination, if there was one. In the second match of the series at Harare on 23rd October, 1999, with Damien Fleming bowling to David Mutendra (the No. 11 batsman), Steve Waugh decided to try his mental disintegration and packed the slip cordon with 9 fielders (the maximum possible):

This was the first and to date only time that such a field setting has been employed in ODI cricket. On the day after this match I recall the Times of India reporting this incident and stating:

Such a tactic had been used earlier in a test by Greg Chappell against New Zealand. At that time the bowler was Dennis Lillee and the batsman was not a tailender, but the top order batsman Glenn Turner.

This tidbit became a rage with trivia buffs and people would ask you to identify the batsman and the bowler from this picture:

The answer, as I always knew, was Glenn Turner and Dennis Lillee. Then I started subscribing to Wisden Asia Cricket in April 2003. The July issue of the magazine had the above picture and the following story as recollected by Lillee himself:

Australia were playing New Zealand in the second test at Auckland in 1977. We were heading for an easy win with more than two days to spare. It was the centenary year and Greg Chappell was about to bring out his book, ‘The 100th Summer’. He had a photographer standing by for the right opportunity, and when their No. 11, Peter Petherick the offspinner, came out, Chappell called all the guys in. I ended up bowling to nine slips, but it was a pretty poor ball. As you can see, Marshy [Rod Marsh] had to go down the leg side to collect. I was trying too hard I suppose. Petherick wasn’t the greatest batsman in the world, but I didn’t get him out for a while that day.

So the answer should have been Dennis Lillee bowling to Peter Petherick! I realized almost four years late that TOI had been misleading.

I have seen several instances where newspapers (and reputed journalists) get their facts wrong. The Times of India is notorious for this. I recently read the film reviewer Nikhat Kazmi claiming that Slumdog Millionnaire was set to become the 4th highest grossing movie of all time worldwide, while the truth is that it was/is nowhere in the top 100.

Indian journalists are notoriously lax in their research, perhaps taking Indian readers for granted. Maybe that is why plagiarists run amok in the Bollywood music industry, because if the journalists did their homework properly and branded every plagiarist a cheat, things would be so much better.